An introduction to the Japanese Collection at Bath Central Library

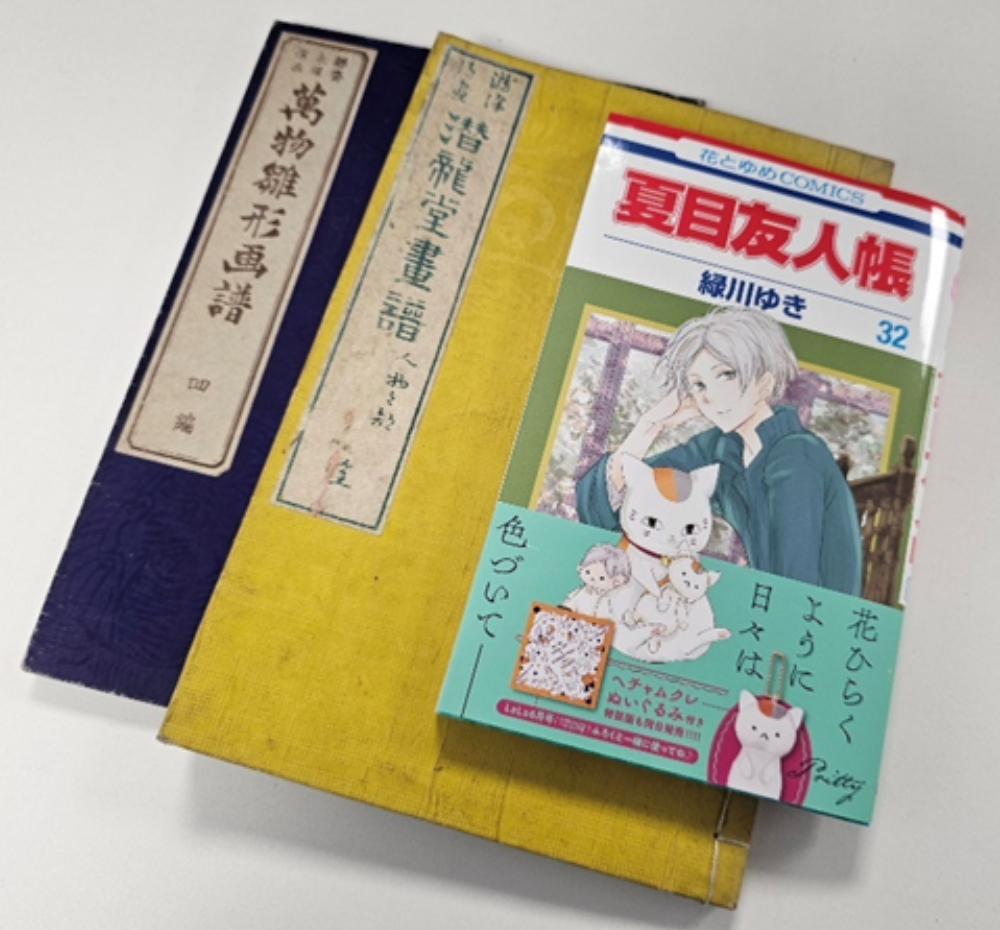

Here at B&NES Libraries we’re lucky enough to have a historic reference collection with all kinds of books spanning hundreds of years. After hosting a Make Mine Mange Exhibition in June 2025, we thought it would be interesting to show you some of the Japanese books in this collection. At the same time, we can shed some light on the question ‘where did manga come from?’

While the postwar influence of internationalisation helped to launch the modern manga industry, artbooks presented in a panelled comic format have been popular in Japan for hundreds of years.

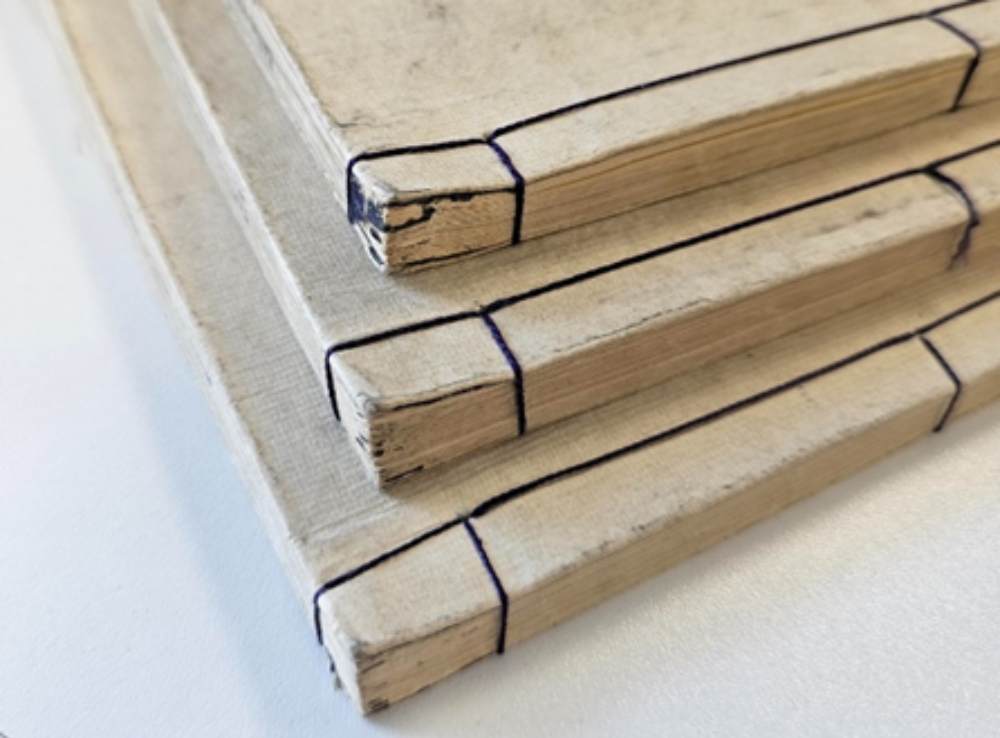

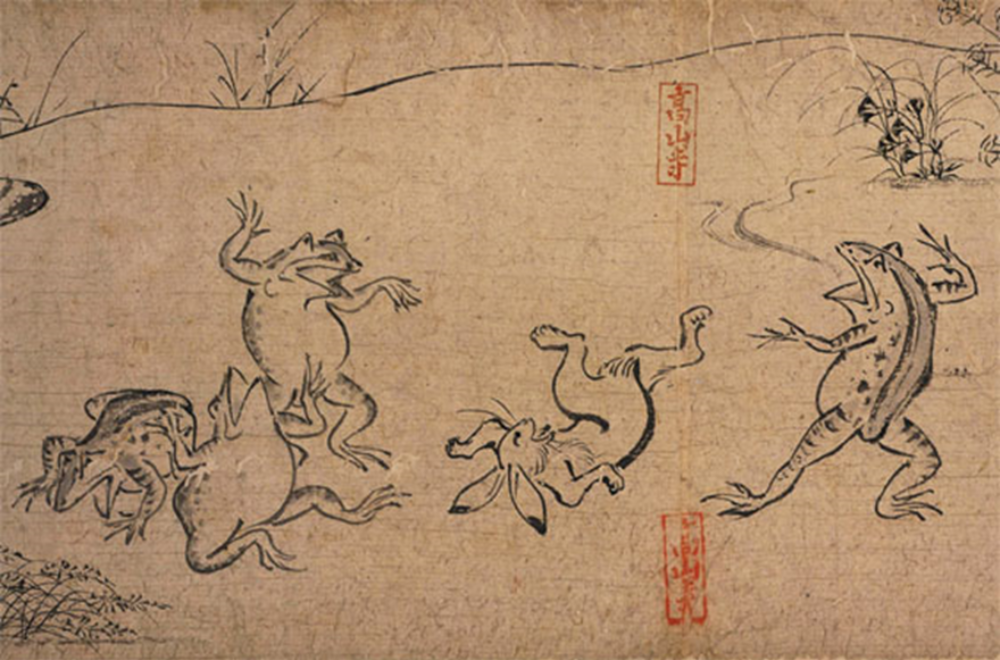

From the tail end of the 8th century, Wasōbon (和装本, Japanese style books) were originally written and illustrated by hand on traditional washi (和紙, Japanese paper), originally glued together to form a continuous scroll or concertina shape, and now usually bound with simple but elegant thread bindings. The famous set of four scrolls comprising the Chōjū-Giga (鳥獣戯画, Animal Caricatures) originally commissioned for Kōzan-ji temple in Kyōto in the 12th century are generally said to be the earliest form of manga in Japan.

Toba Sōjō (attr.) – Kyōto National Museum

Utagawa Kunisada – Tokyo Central Library

Our wasōbon date mostly from the Meiji Era (1868-1912) – a period of rapid internationalisation and mechanisation, which brought with it affordable mass-produced paper and woodblocks for the printing of books. Wasōbon were published at speed, sometimes across long print runs and multiple volumes under the same title – which can lead to some cataloguing headaches!

The British Museum, the Smithsonian Institute, and the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art all hold wasōbon from the same series as ours, some of which are identical, and some of which are adjacent editions or volumes published in different years.

Katsushika Hokusai – New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

You may recognise some of Japan’s famous Ukiyo-e (‘floating world’) masterpieces, such as Katsushika Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa – many of these famous images (which we tend to enlarge in our minds, in keeping with their cultural significance) were actually small prints, produced in numbers for popular consumption, just like our modern manga.

The same is true of many wasōbon, which included art books and illustrated stories by the ukiyo-e masters. In a way, these books are progenitors of our Marvellous Manga.

Let’s take a look at the Wonderful Wasōbon held at Bath Central Library!

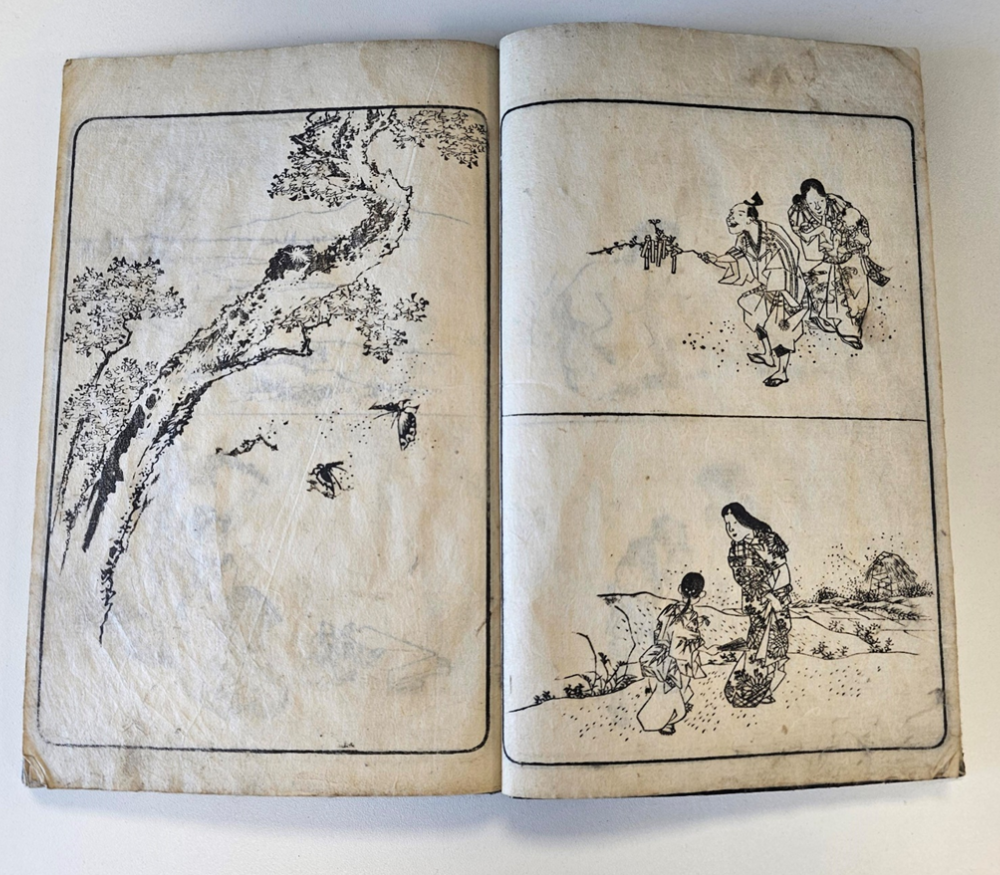

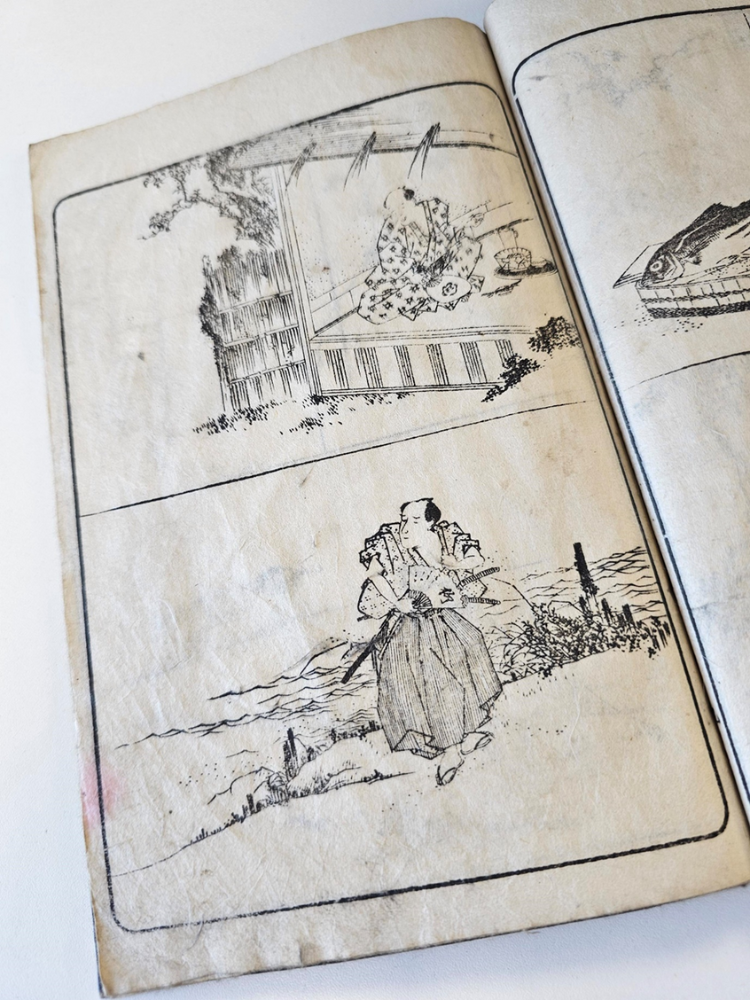

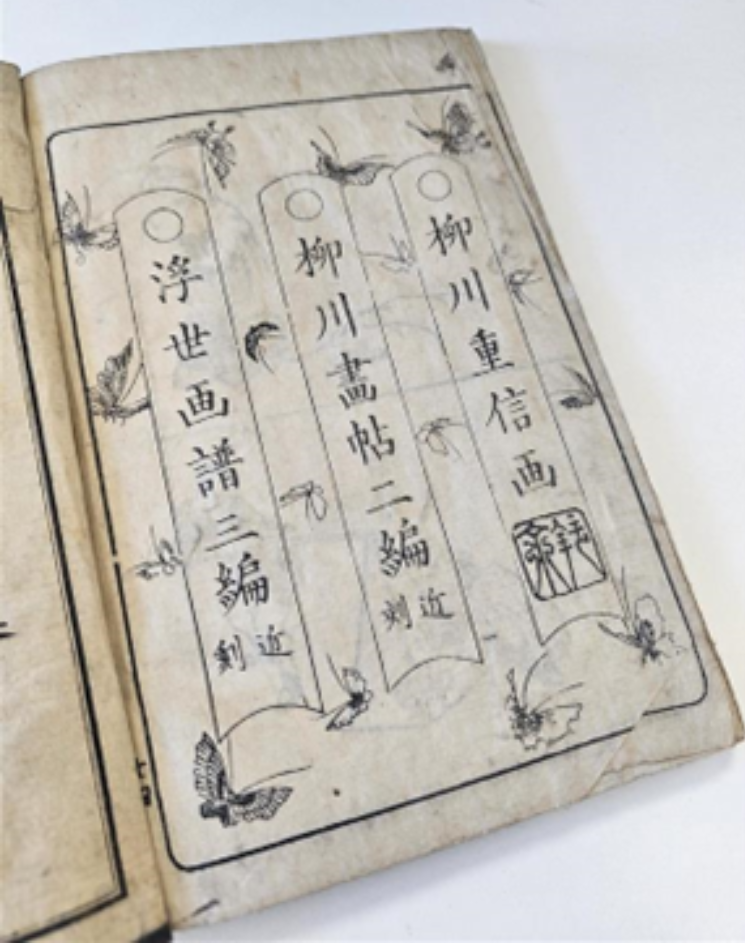

Yanagawa Shigenobu’s Pictures 柳川重信画 (ca. 1832)

Yanagawa Shigenobu 柳川重信 (1787-1832)

This is the oldest wasōbon in our collection, dating from the late Edo period (1603-1867) and printed on handmade washi. Yanagawa was a student (and later son-in-law) of Hokusai himself, specialising in ‘surmino’ – inset illustrations for novels, although this book (like the others in our collection) is presented as selection of panelled illustrations, showing us an early example of a comic-type layout nearly two centuries ago.

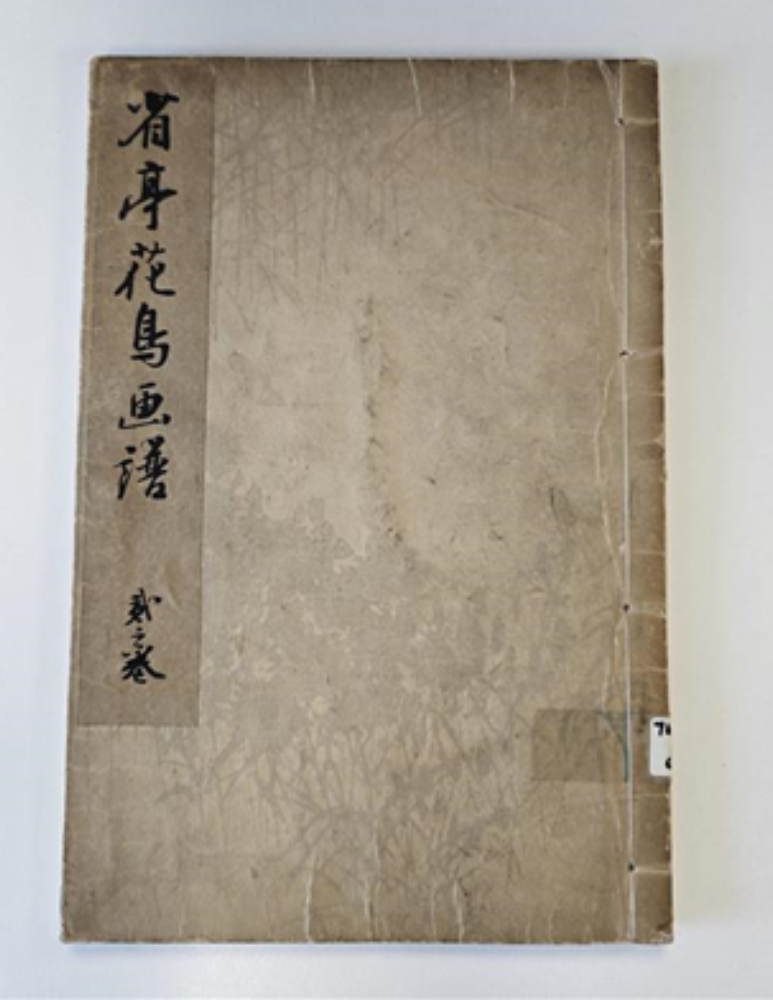

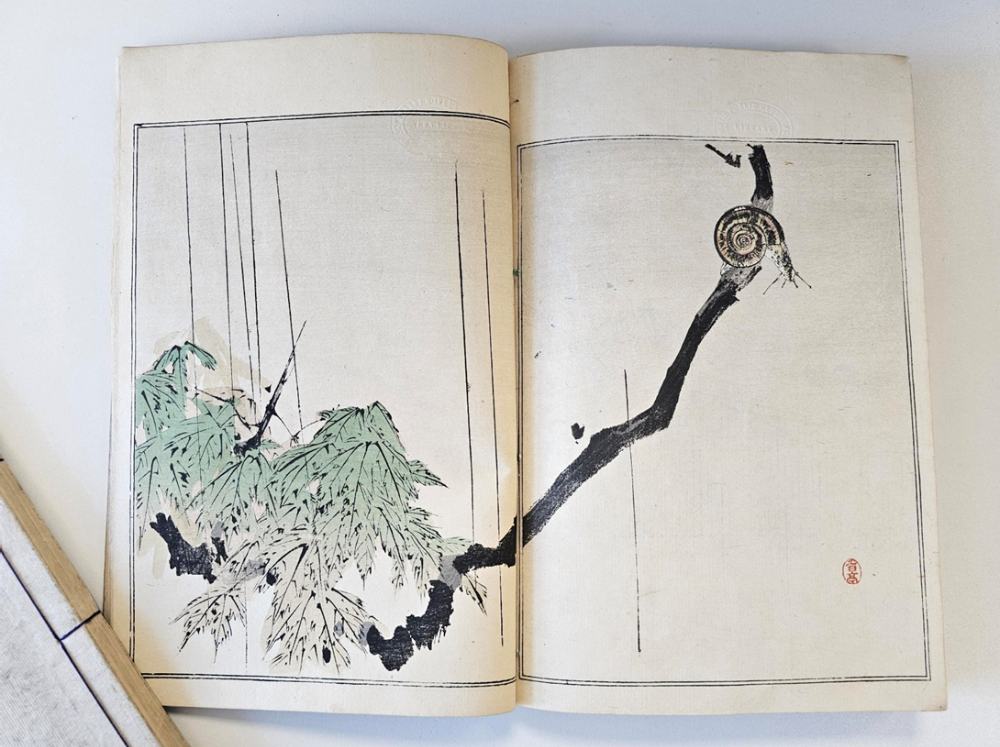

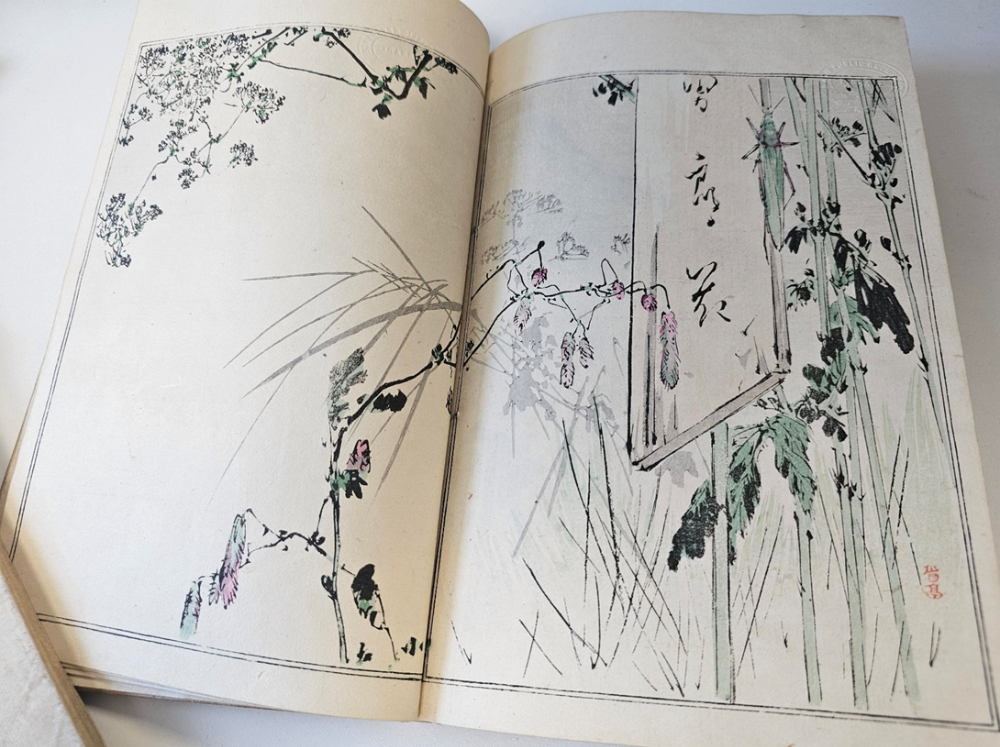

Seitei’s Kacho-ga Album 省亭花鳥画譜 (1890)

Watanabe Seitei 渡辺省亭 (1851 – 1918)

Kachō-ga or kachō-e (flower and bird pictures) evolved in both Japan and China from historic Chinese techniques. Commonly rendered in English as ‘the poetry of nature,’ this striking style became wildly popular in the 18th century, and has remained in fashion ever since.

Kachō-ga celebrates the beauty of the mundane by transforming everyday parts of nature and scenery into stunningly evocative images with a powerful aura of nostalgia. This is a theme which we’ll see repeated in these books, and which continues in modern media – perhaps most famously exemplified today by the films of Studio Ghibli.

Watanabe was one of the first Japanese artists to travel widely in Europe, residing in Paris for three years from 1878, which allowed him to distil fashionable European techniques into a unique new style. Watanabe managed this at a time when Japan was still emerging from self-enforced isolation, so this was quite the advantage over his peers – we know that he was working for the Kiritsu Trading company in 1875

Kiritsu sold tea and mass-produced art (which is where Watabnabe came in) for the export market, and its cofounder Matsuo Gisuke had society connections, which may have helped to grease the wheels for Seitei’s exit permit.

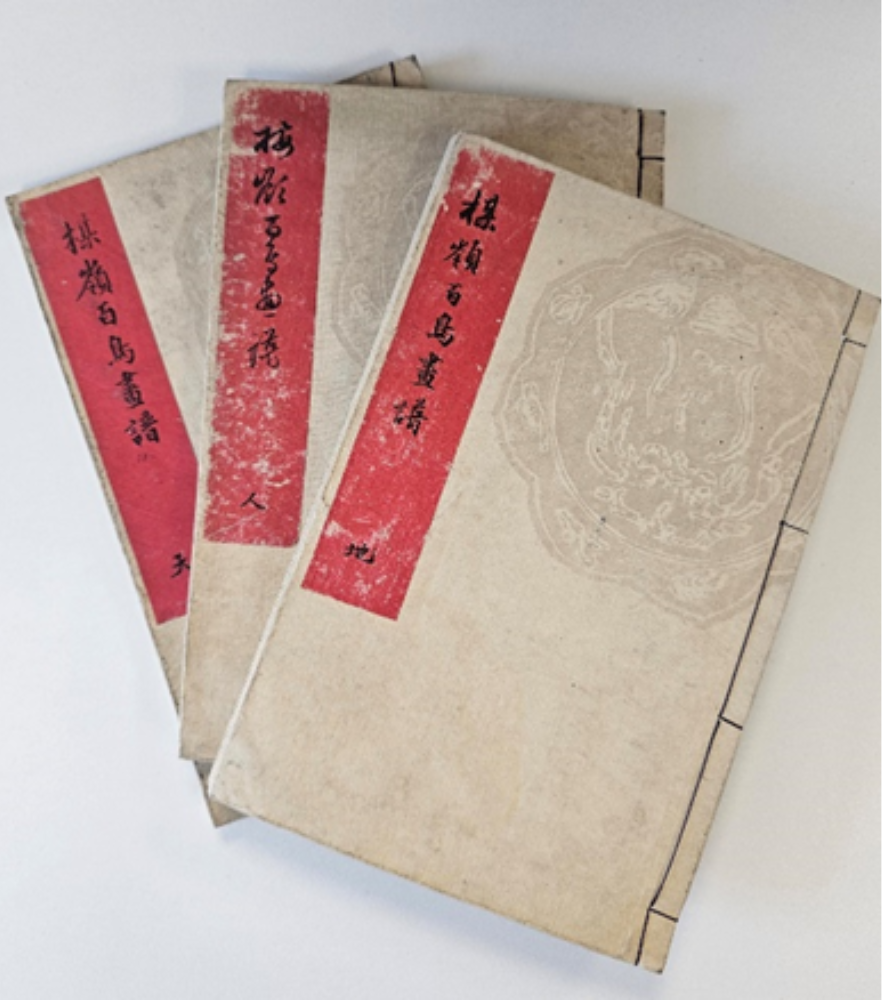

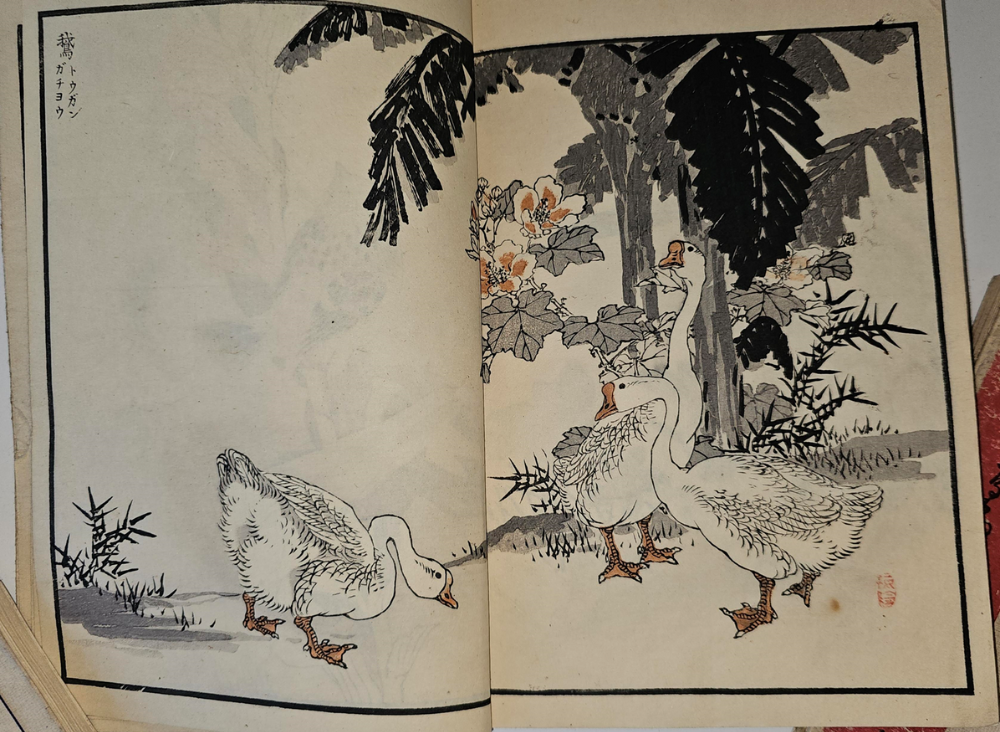

Bairei’s One Hundred Birds 楳嶺百鳥畫譜 (1881)

Kōno Bairei 幸野楳嶺 (1844 – 1895)

This is another example of Kachō-ga focussing on birds in botanical settings. There are three sumptuously illustrated volumes labelled Heaven, Man, and Earth (天, 人, 地). The bold prints and dusky colours are incredibly eye-catching, which is to be expected given that artist Kono Bairei was regarded as a master of Kachō-ga, working and teaching art from his Kyoto studio.

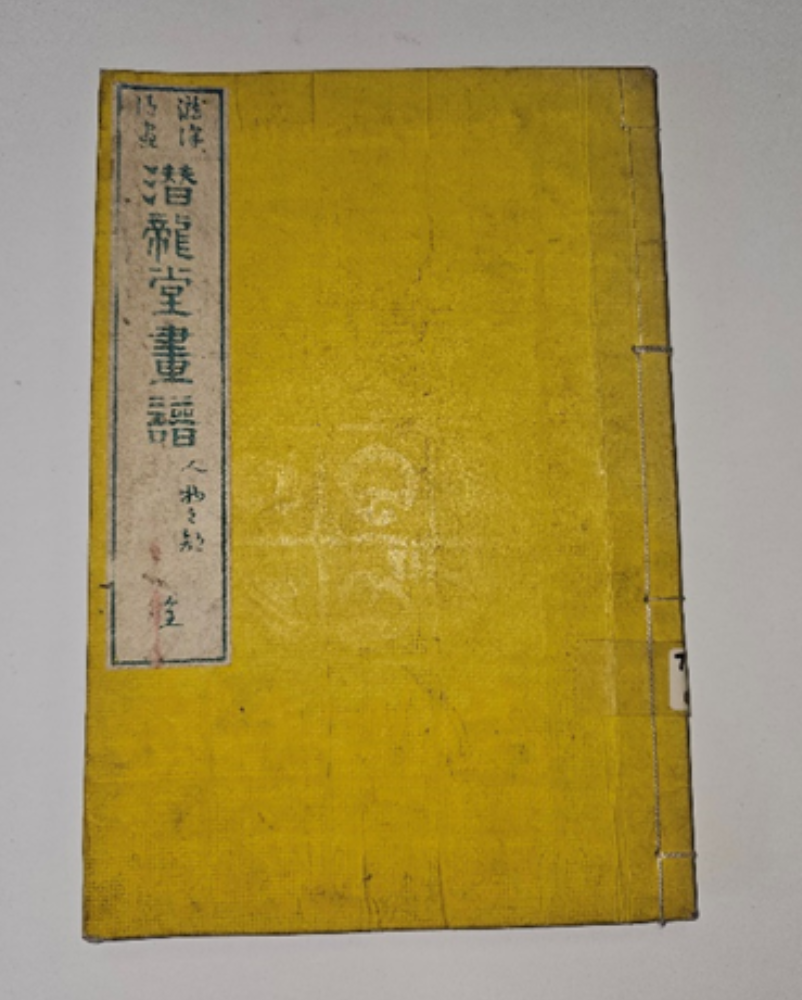

The Senryūdō Album 潜龍堂画譜 (1882)

Takizawa Kiyoshi 瀧澤清 (18?? – )

This book is a bit of a mystery! Clues about Takizawa are sparse – contemporary evidence that he existed at all sees limited to catalogue entries for his artbooks, scattered across the websites of libraries and booksellers. A few different examples of his work remain, published as different volumes of the same title Senryūdō-gafu some of which focus exclusively on nature kachō-ga, and some of which continue the theme of spirits and nature entwined as seen in our volume.

The first thing that leaps off the page here are the asymmetrical panels – it bears a striking resemblance to a modern comic book. The scenes depict the coexistence of mortal and supernatural life in the countryside – poets chant, fishers fish, and a girl tends to her horse; while gods frolic, a wind sprite sails down the river on an umbrella, and a group of good-luck spirits catch paper cranes from the sky with a fishing rod.

This tight weave of the supernatural and the worldly is a keynote in Japanese folklore. Walking close beside the themes of kachō-ga -ga, this idea continues to flourish in modern manga, although it can look very different!

The crane-catching kami from Senryūdō shown alongside a vampire, Gorgon, and oni enjoying a drink in the 2025 manga artbook Yōkoso Himitsu Toshōkan (ようこそ秘密図書館 , Welcome to the Secret Library) by @Avogado6

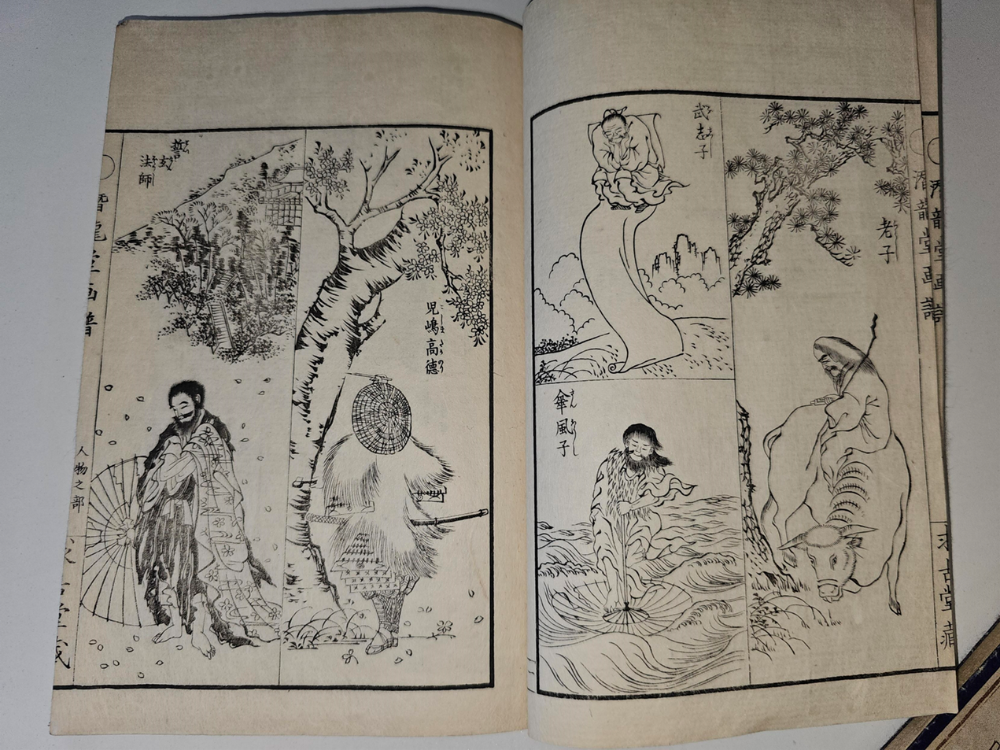

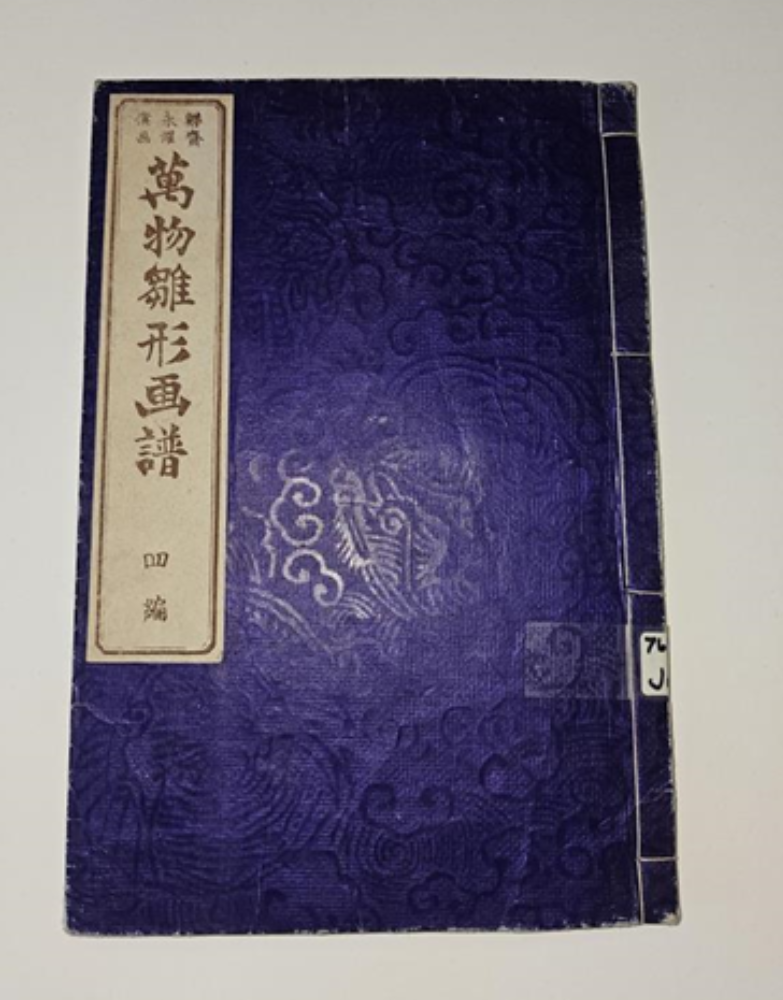

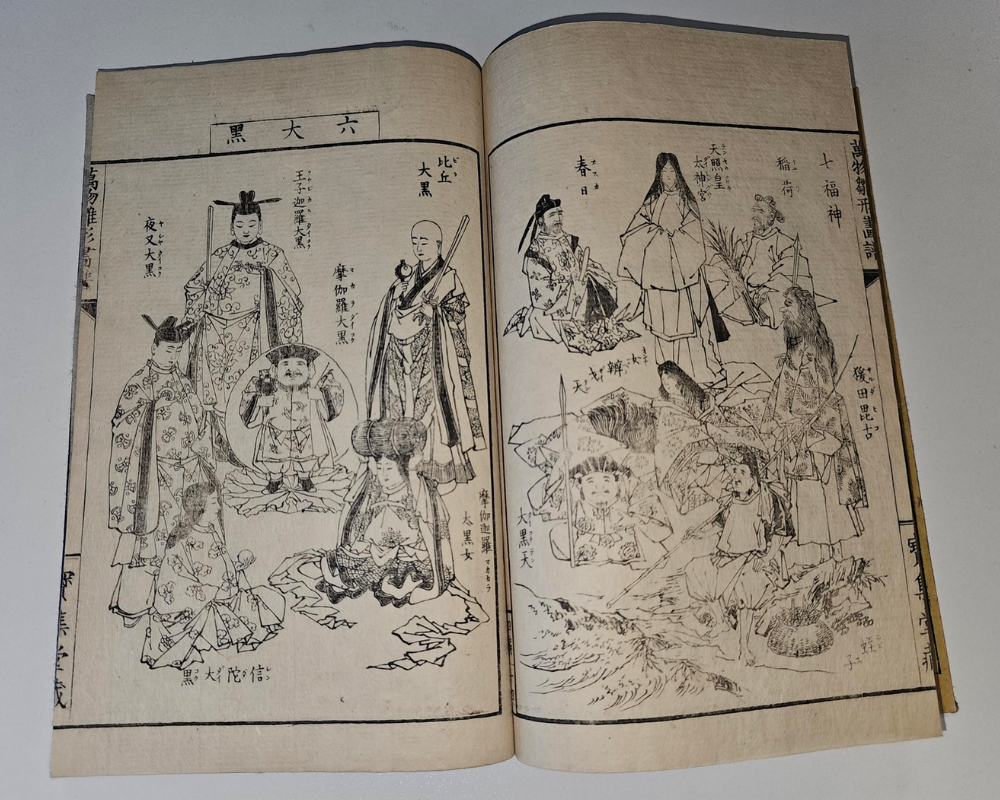

The Artbook of All Things 萬物離形画譜 (1881)

Sensai Eitaku 鮮斎永濯

Continuing in the animist theme, this book shows Shinto kami (gods) and Buddhist monju (bodhisattva)in exquisite detail. It also contains illustrations of sacred statuary and even a series of pattern prints with folklore themes.

Kami include not just the major gods, but also the spirits of the hearth and the natural world. Monju are individuals who are established on the path to Buddhahood, but have not yet fully traversed it, reinforcing the close connection between our world and the divine.

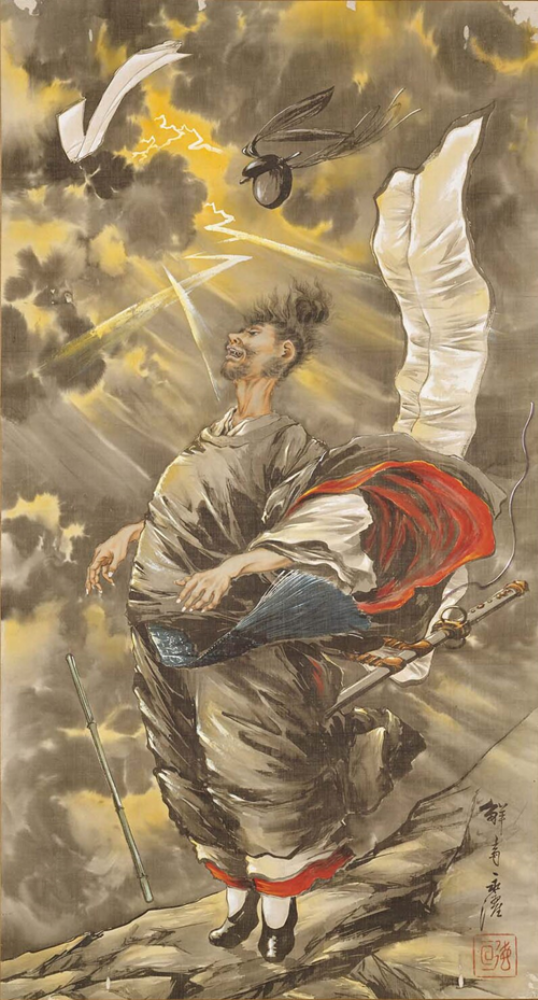

Sensai Eitaku appears to be a pseudonym of Kobayashi Eitaku, who struggled with critical reception during his lifetime. Some of his later work bears a striking resemblance to modern comic art, and he now enjoys a considerable legacy.

Sugawara Praying on Mt. Tenpai (1880)

Kobayashi Eitaku / Boston Museum of Fine Art

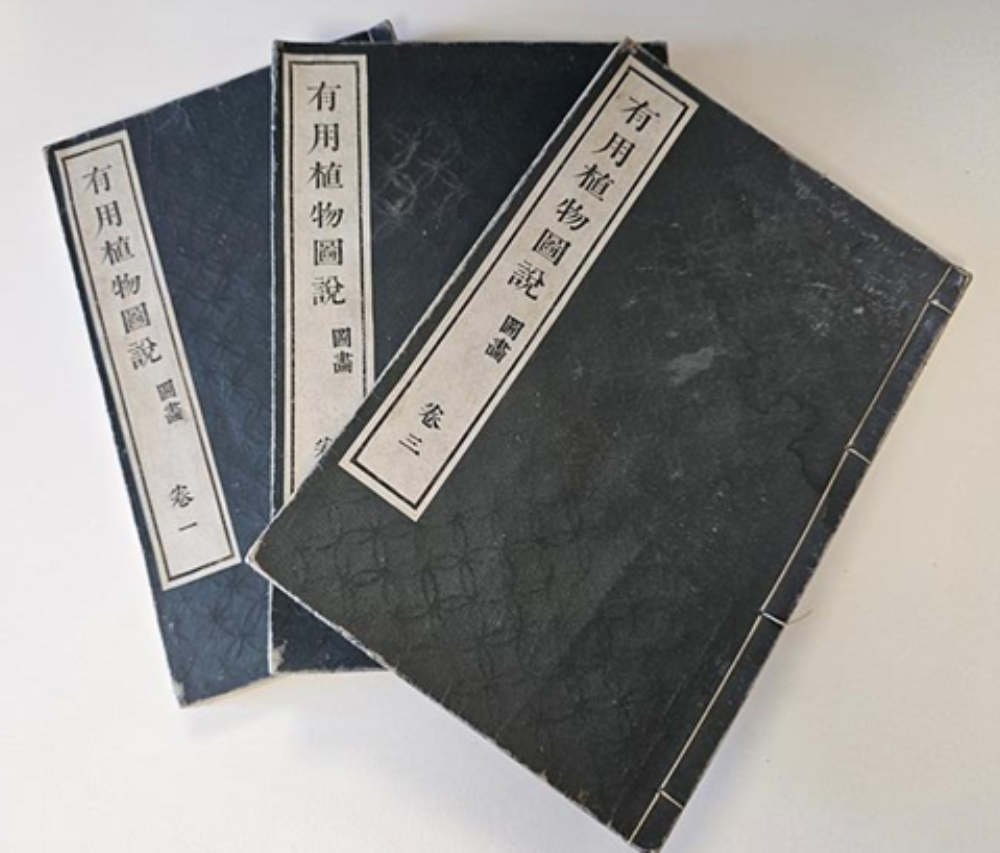

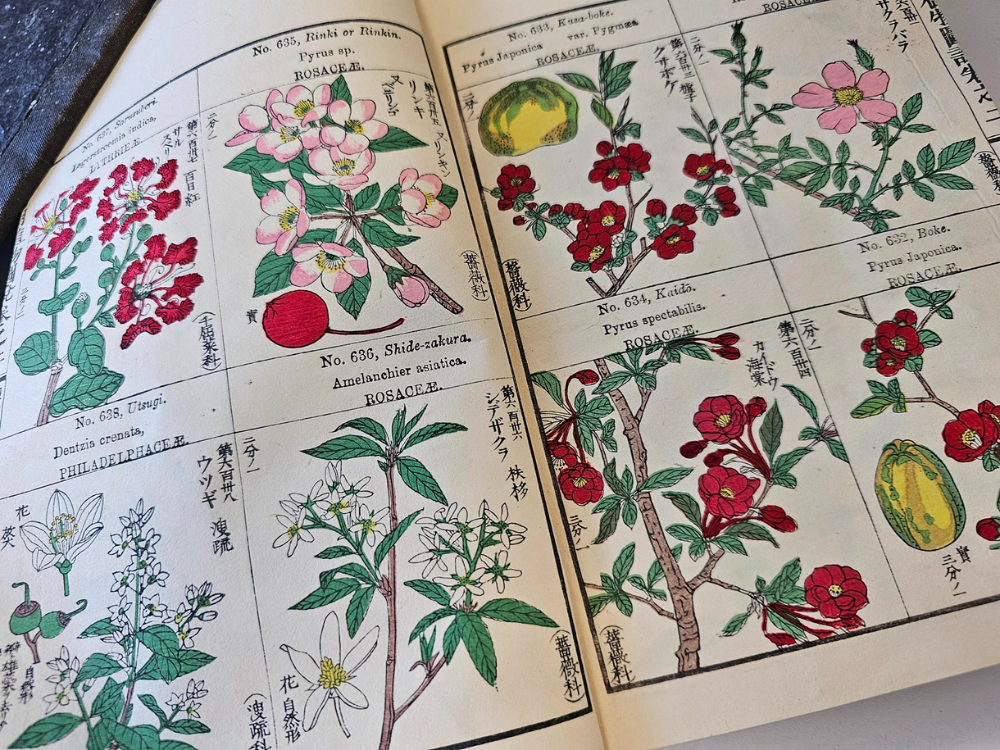

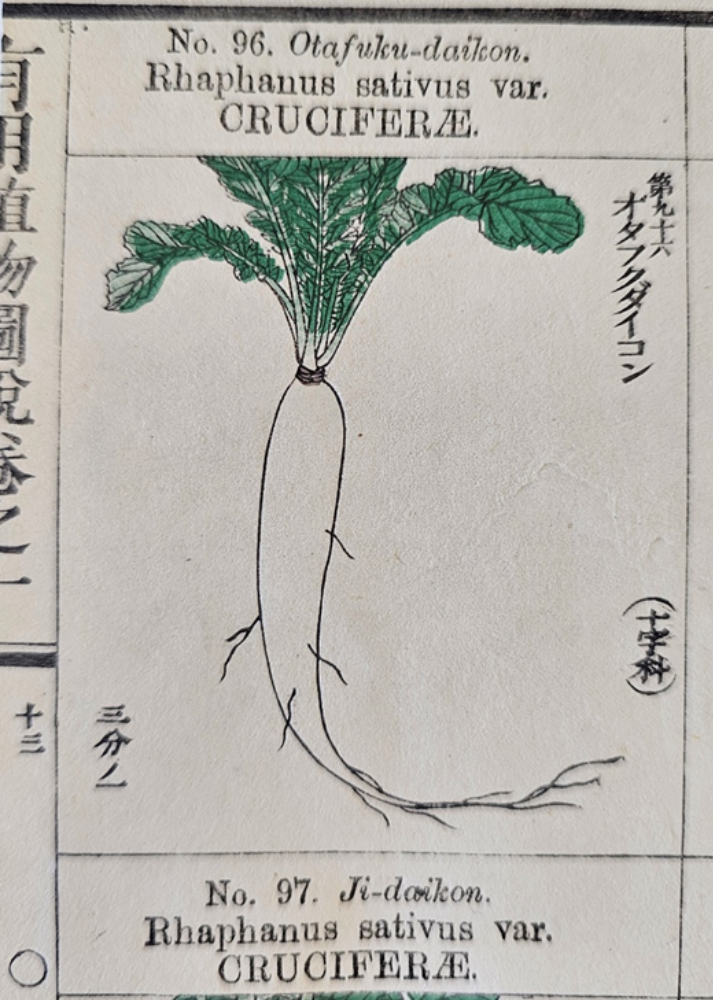

Useful Plants Illustrated 有用植物圖説 (1891)

Tanaka Yoshio 田中芳男 (1838 – 1916)

The last book in our collection is a little different to the others, as it’s a non-fiction book not intended for viewing pleasure. It’s still beautifully illustrated, with detailed botanical woodblocks on a pleasingly symmetrical grid.

Author and illustrator Baron Tanaka Yoshio was a civil servant with a passionate interest in natural history, and was responsible for devising both the Japanese and Latin taxonomy (species names) of native Japanese plants, many of which are shown in the tomes of this botanical encyclopaedia.

Tanaka famously established Ueno Zoo in 1882 (which remains a popular attraction today) and was also involved in setting up the University of Tokyo’s department of agriculture, the Japan Agricultural Society, the Japan Forestry Society, and the Japan Fisheries Society.

Today these books are held in the closed access reference collection at Bath Central Library. Most of our closed access reference books can be viewed on request by any visitor, but we have to be careful about access to the wasōbon due to their fragile construction.

If you’d like to know more, please email stock_team@bathnes.gov.uk for a chat.