An introduction to our Fashion Collection

Fashion Museum Bath is the UK’s largest museum dedicated to the transformative power of fashion. The new Fashion Museum will be opening 2030 with a pioneering collection to inspire, challenge and spark ideas. It will champion fashion’s transformative power as a global industry and expression of creativity, culture and identity bringing fashion to life for local and national audiences.

We’re supporting the museum while it’s temporarily closed with our brand new Fashion Collection at Bath Library.

Visit https://www.fashionmuseum.co.uk/ to find out more.

Our fashion collection has been created to act as an important resource for anyone studying fashion.

Found in Bath Central Library, it’s made up of reference titles from our Historical Reference Collection, and more modern borrowable titles. The older reference titles are kept in the stack and the newer titles can be found in our Non Fiction section. We also have the Country Life magazine from 1897-2019 which often include full page fashion adverts. These are kept in the stack at Bath Library.

Additionally, we have a subscription to the Berg Fashion Library, which is free to access online for any library borrower, at home or in our libraries.

The titles in the collection cover periods across history, but are particularly focussed on 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. They cover fashion theory, textiles and include dictionaries and glossaries. Well known authors include Phillis Cunnington and Janet Arnold.

This virtual exhibition gives a glimpse of the subjects and illustrations contained in our Historic collections, you can also see a curated list of our borrowable recommended reads.

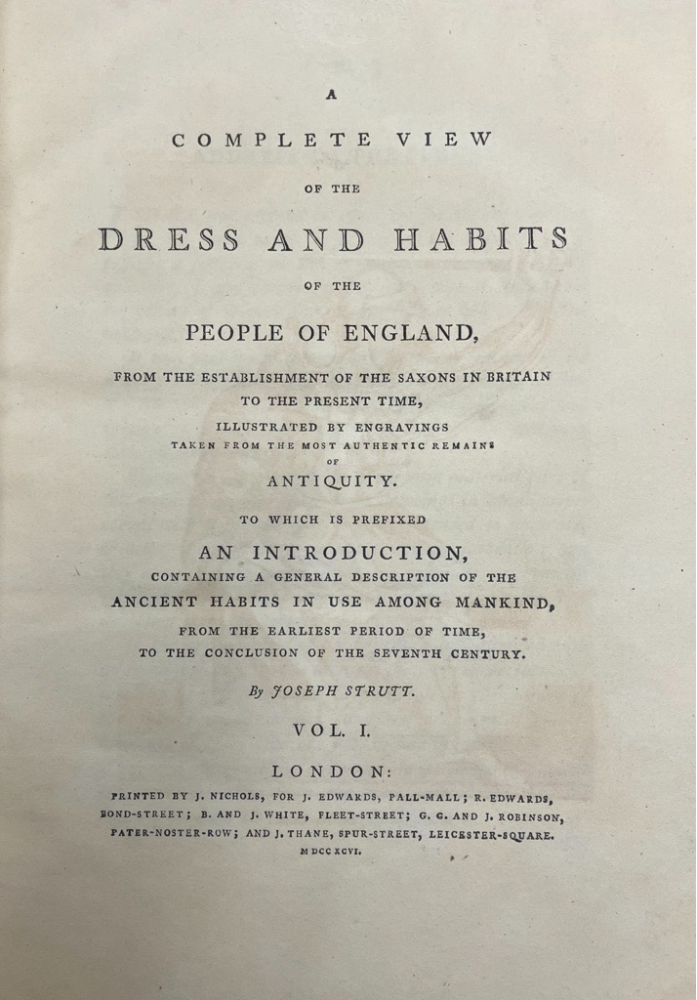

A Complete View of the Dress and Habits of the People of England, from the Establishment of the Saxons in Britain to the Present Time – Volume I

by Joseph Strutt 1798

Descriptions of dress and habits in Britain from the Anglo-Saxons to 14th Century. Includes colour illustrations. HRC Ref: 391 STR

Joseph Strutt (1749-1802) was an English engraver, artist, antiquary and writer. Strutt was a Royal Academy student from 30th January 1769. He is today most significant as the earliest and “most important single figure in the investigation of the costume of the past”.

“At the time of their establishment in England we find that they were well acquainted with the manner of dressing and spinning flax, which they manufactured into cloth, and dyed of various colours according to their fancy; and, from the high price of wool enacted by the Saxon Legislature, a strong presumptive proof may be drawn, that the making of woollen garments was also practiced in this kingdom.”

on the Anglo Saxon Period 410 to 1066

Young Women from the 13th Century

1201-1300

Example of the vibrancy of the hand-coloured engraved plates in this volume.

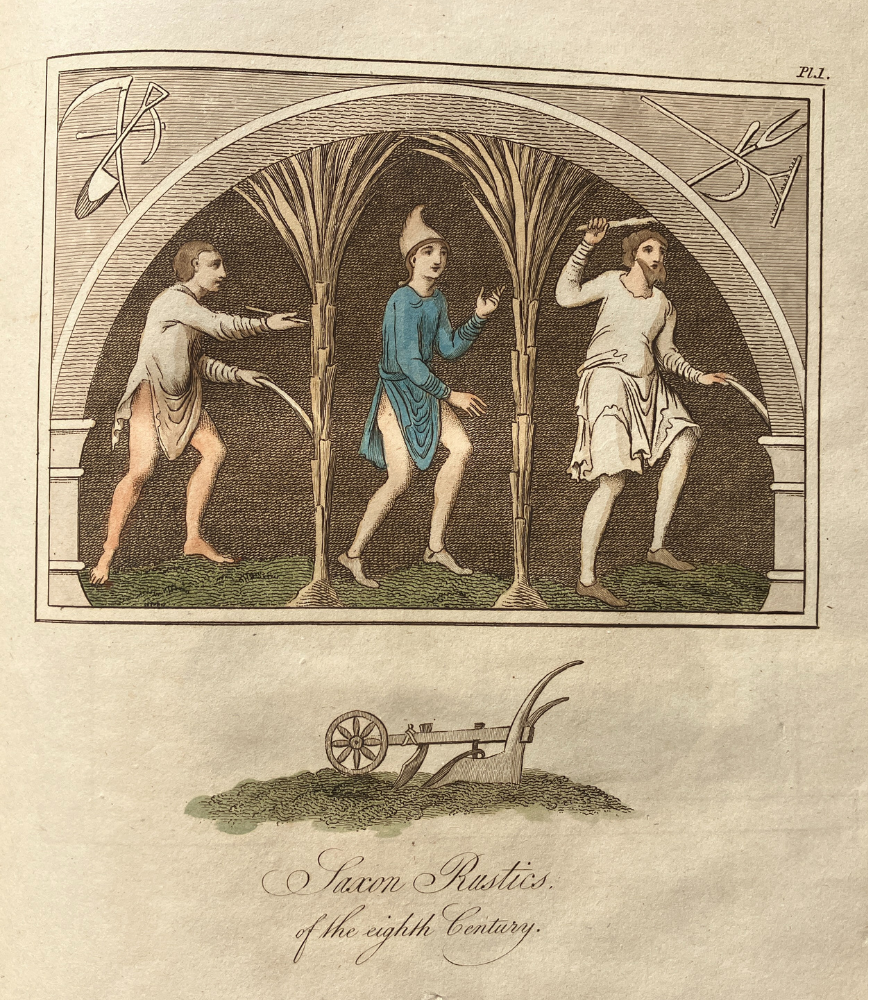

Saxon Rustics of the Eighth Century

701-800

“Two specimens of the open tunic: The figure to the left represents a ploughman; and is the only instance in which the tunic is depicted without a girdle round the loins. The third figure is also a ploughman, but of superior rank, and probably a free man; for; the tunic open on the sides appears to have been, at this period at least, the distinguishing badge of slavery or servitude.”

Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages

by Henry Shaw 1858

A history with illustrations detailing the dress and decoration in Britain from 410 to 1402. HRC Ref: 391 SHA

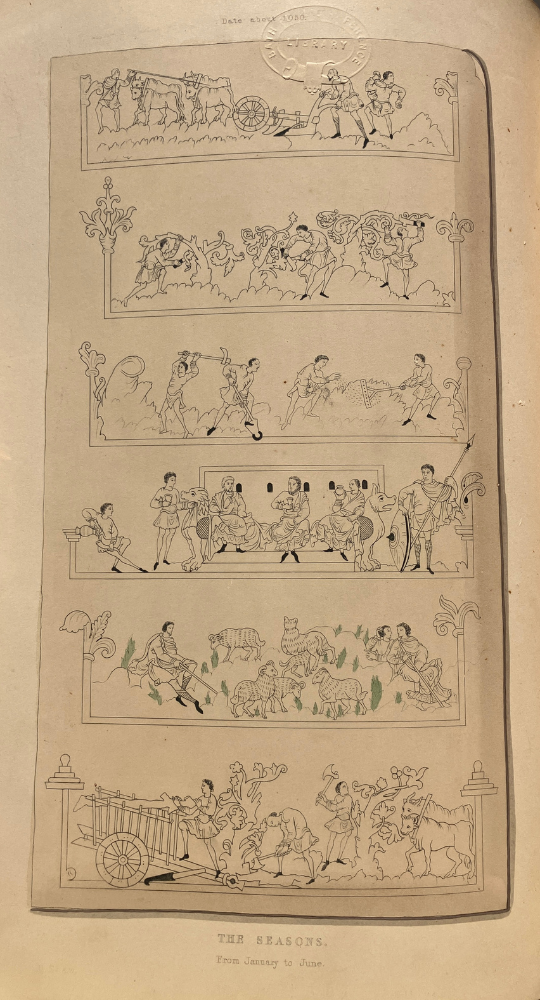

The Seasons. From January to June.

(late Anglo-Saxon)

“Different ancient manuscript calendars furnish many curious illuminations illustrating country life among our ancestors. To the tables of different months were frequently added pictures representing the agricultural labours, sports, or ceremonies which characterized each.

The series are taken from an Anglo-Saxon calendar, written (as it appears) a few years before the Norman Conquest. These drawings are very valuable illustrations of the costume and manners of our Saxon forefathers.”

Ladies Playing on the Harp and Organ C14th.

“Costume, in the West of Europe, during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, was not strikingly characteristic of difference of countries; its changes were frequent, and often remarkable, but the intercourse between England and France, and in some measure with the neighbouring states, was so constant that these changes were nearly simultaneous in them all. When, however, we pass to the south, and enter the warm clime and free states if Italy, we find the dresses of all classes have an entirely different character. The costume of ladies, in particular, was there extremely light and graceful. Our plate represents two ladies of Siena, in the costume of the beginning of the fourteenth century.”

A Cyclopaedia of Costume of Dictionary of Dress – Vol. I. – The Dictionary

by James Robinson Planche 1876

An a-z encyclopaedia detailing items of fashion in Europe from 1st Century AD to 1760. HRC Ref: 391 PLA

James Robinson Planché (1796-1880) was a multifaceted English playwright, antiquarian, and historian known for his significant contributions to 19th-century theatre. Planché was also deeply invested in the accurate representation of British costume in theatrical productions, which led to his influential publications, “History of British Costume” and “A Cyclopaedia of Costume.”

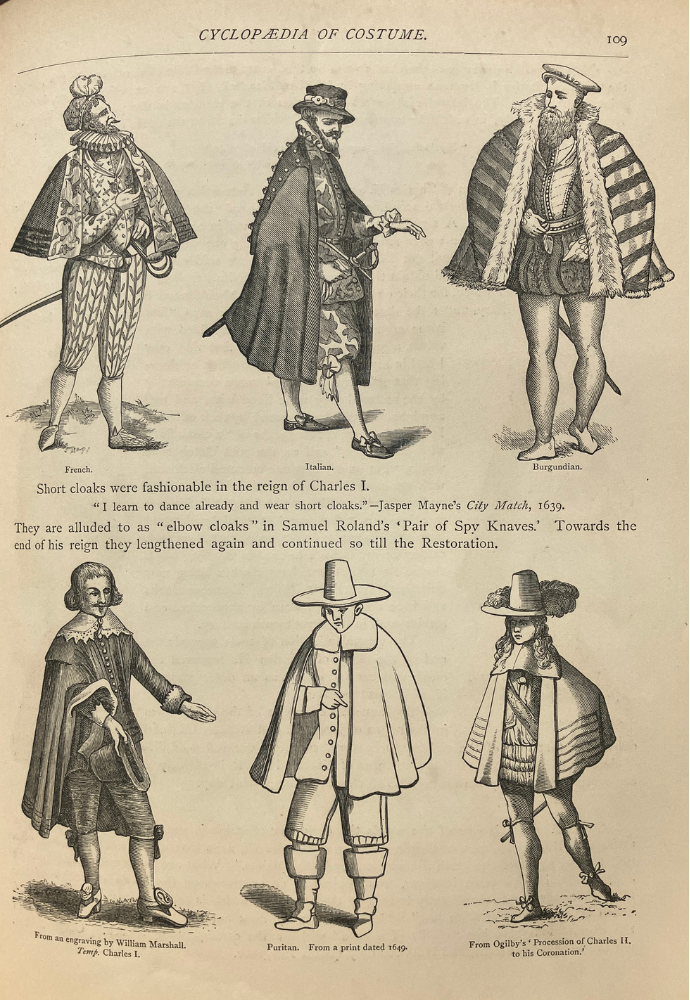

CLOAK. (Klocke, Flemish ; cloca, Latin.)

“Under one name or another this familiar garment has existed time out of mind in nearly all countries. The word “cloak” in English is derived, according to Skinner, from the Saxon lach, but the usual term for the garment in Saxon is mentil, as in French it is manteau, from whence our word “mantle”, more especially appropriated by us to a robe of state, under which head the mantles worn by sovereigns and the nobility on occasions of ceremony will be considered separately.”

Short cloaks were fashionable in the reign of Charles I (1625-1649).

“I learn to dance already and wear short cloaks.” – Jasper Mayne’s City Match, 1639

“They are alluded to as “elbow cloaks” in Samuel Roland’s ‘Pair of Spy Knaves.’ Towards the end of his reign they lengthened again and continued so till the Restoration.”

Chromolithograph of the effigies at Fontevraud of Henry II (1133-89), Eleanor de Guienne (1122-1204) and Richard Coeur de Lion (1157-99).

“MANTLE. Henry II. obtained the sobriquet of “court manteau”, in consequence of his introduction of the short cloak worn in the province of Anjou. The regal mantle of that date could not be more satisfactorily illustrated then by the effigies of King Henry himself, his queen, and of their eldest son, the lion-hearted Richard.”

English Costume – IV Georgian

by Dion Clayton Calthrop 1906

A visual guide to the history of English fashion with illustrations. Volume four, the Georgian period. 1660-1830. HRC Ref: 391 CAL

George the Third (reigned 1760-1820).

“Throughout this long reign the changes of costume are so frequent, so varied, and so jumbled together, that any precise account of them would be impossible. I have endeavoured to give a leading example of most kind of styles in the budget of drawings.”

A Man of the Time of George III.

“The full-skirted coat, though still worn, has given way, in general, to the tall-coat. The waistcoat is much shorter. Black silk knee-breeches and stockings are very general.”

A Woman of the Time of George III.

“In the earlier half of the reign. Notice her sack dress over a satin dress, and the white, elaborately made skirt. Also the big cap and curls white wig.”

“Women – you may watch the growth of the wig and the decline of the hoop. You may see those towers of hair which there are so many stories. Those masses of meal and stuffing, powder and pomatum, the dressing of which took many hours. Those piles of decorated, perfumed, reeking mess, by which a lady could show her fancy for the navy by balancing a straw ship on her head. Heads which were only dressed, perhaps, once in three weeks, and were then re-scented because it was necessary. Monstrous germ-gatherers of horse-hair, hemp-wool, and powder, laid on in a paste, the cleaning of which is too awful to give in full detail.”

A Man of the Time of George III.

“The cuffs have gone, and now the sleeve is left unbuttoned at the wrist, The coat is long and full-skirted, but not stiffened. The cravat is loosely toed, and the frilled ends stick out. These frills were, in the end, made on the shirt, and were called chitterlings.”

A Woman of the Time of George III.

“This shows the last of the pannier dresses, which gave way in 1794 or 1795 to Empire dresses. A change came over all dresses after the revolution.”

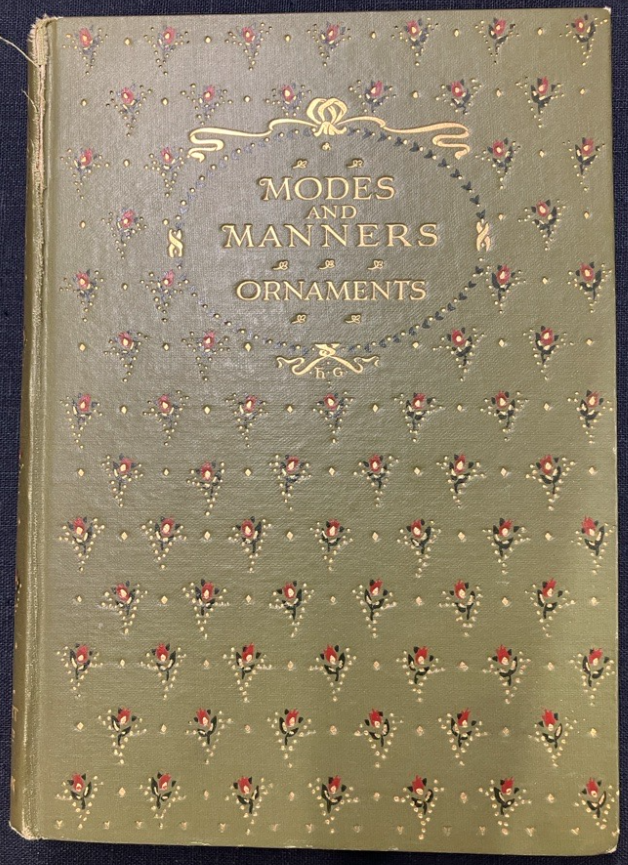

Modes & Manners; Ornaments

by Max Von Boehn 1929

A History of lace fans, gloves, walking-sticks, parasols, jewelry and trinkets in Europe, up to and including the C19th. HRC Ref: 391 BOH

“Of the two near relations, the sunshade and the umbrella, the sunshade is the older, and that by some two thousand years. It comes from the East, where the climate makes some shelter from the sun’s fierce rays imperative. It was and is a useful, indeed an indispensable, adjunct of life in hot countries.

In ancient Rome the umbrella as a protection not against the sun, but against rain, appears to have originated.

It was among the English public, in particular, that the umbrella – or rather the sunshade – achieved a certain fame through the part it played in Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, one of the most widely read books in the literature world. After the appearance of this novel in 1719 the sunshade was for a time known in England simply as the “Robinson”.”

Classical Greek Lady with a Parasol.

From a vase painting in the Hamilton Collection.

Vienesse Mode 1822.

“Umbrellas, we have been told, were first seen in Venice in 1739 and sunshades about 1760, but pictorial art tells a different story. The Venetian painters knew the umbrella much earlier and it may be seen in Tiepolo’s frescoes in the Villa Valmarana which date from the midway in the seventeen-thirties.”

Bertuch’s “Journal des Luxus und der Moden,” 1798

“As early as 1710 one Marius of Paris had invented an umbrella with a jointed stock which could be folded together at the joint, placed in a case and carried in the pocket. This invention seems not to have fulfilled the expectations based upon it, for it vanished without leaving a trace behind.”

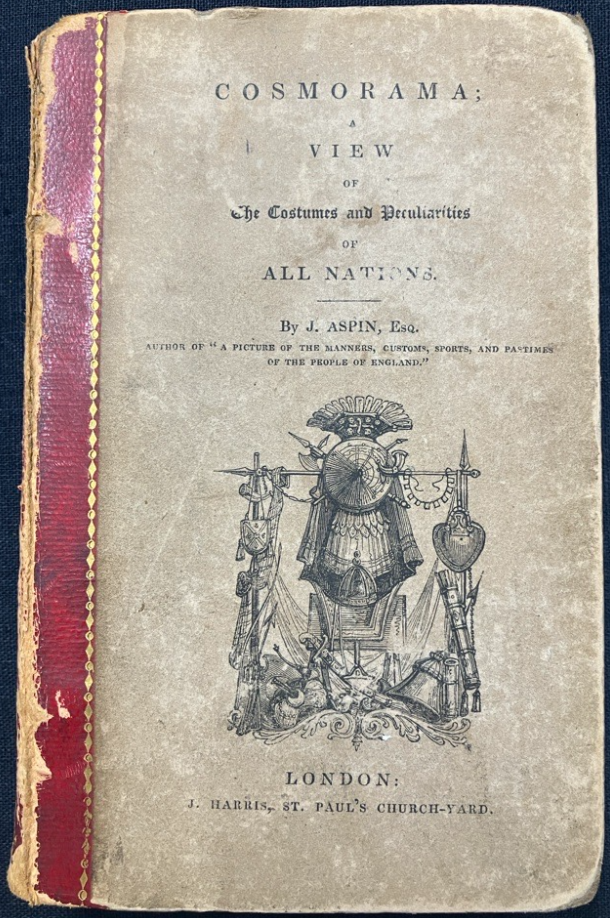

Cosmorama; a View of the Costumes and Peculiarities of All Nations

by J. Aspin 1827

Miniature renderings of typical dress from every country around the world, as well as descriptions of societies and customs. HRC Ref: 391

Jehoshaphat Aspin (fl. c. 1805 – c. 1832) was a British author, humourist, historian, and geographer active in the early 19th century. The name is believed to be a nom-de-plume for an unknown female author.

“The higher classes of the English observe great simplicity in their dress, except on public occasions, when they display much of elegance and somewhat of magnificence.

The dress of the women is, like that of the men, almost uniform; although fashions change in England oftener than in any other country. Cotton and woollen stuffs, of which the texture, fineness, and patterns, are almost infinitely varied, constitute the basis of it.”

Londoners 1827.

“Young people in the metropolis and large towns are fond of showy apparel, which the improved state of the manufactures enables them to indulge in at an easy rate. Hence, on Sundays and holidays, apprentices and servants appear in all the gaiety of persons of rank and fashion: and the lowest tradesman endeavours to make a respectable appearance.”

English Peasants 1827.

“Large scarlet cloaks, with bonnets of straw or black silk, which preserve and heighten the fairness of their complexion, distinguish the country women which come to market. And the working farmer preserves his clothes by a covering in the shape of a shirt, of white, brown, or blue dowlass.”

The History of Underclothes

by C. Willet & Phillis Cunnington 1951

A well-documented, illustrated volume by two clothing historians who consider undergarments worn by the English over the past 600 years. HRC Ref: 391 CUN

1841-1856 – Men – The Shirt

“About 1850 the bottom of the shirt, front and back, which had hitherto been cut square, was beginning to be cut in a deep curve, as illustrated in an advertisement of 1853. This curve persisted well into the twentieth century.

For evening dress the ‘Patent Elliptic Collar’ – cut higher in front than behind – was introduced. ‘How gloriously he is attired…. His elliptic collar, how faultlessly it stands; his cravat, how correct; his shirt how wonderfully fine; and oh! how happy he must be with such splendid sparkling diamond studs – such beautiful amethyst buttons at his wrists – and such a love of a chain of disporting itself over his richly embroidered bloodstone-buttoned vest…. Altogether such a first-class swell is rarely seen….’”

1909-1918 – Women – The Chemise

“This was in the empire style, often square-cut with narrow shoulder straps, and the top enriched with insertion. Nainsook was a popular material.

Although the garment lost favour it by no means disappeared; thus in 1917, ‘crepe de Chine chemise, vandyked edge, ribbon-slotted waist, ribbon shoulder strap, in white, sky, pink and helio, 24/6,’ was being advertised.”

Our Historical Reference Collection can be viewed on request.

If you’d like to know more, please email stock_team@bathnes.gov.uk for a chat.